The Count That Couldn’t

From Vague Prompts & Poor Planning to Hallucinations & False Fixes

This first in a five-part series documenting my attempt to measure the AI and human contributions in AI-augmented writing. What began as a simple experiment with vague prompts and weak planning turned into a cautionary tale about hallucinations, lost context, and the real cost of trusting AI too much.

• Part 1: The Count That Couldn’t

• Part 2: Algorithmic Theatre

• Part 3: Crash Course in Collaboration

• Part 4: Victory in a New Venue

• Part 5: Not Magic, Beyond Measure

TL;DR: After 45 hours, my initial attempt to measure the true author of contributions to articles had failed. What began as a simple JSON object became a mess of Python scripts, fictional functions, and AI claiming success while churning out empty files. The hard lesson is that the “Human Tax” of inadequate preparation can cost as much as any “AI Tax.”

I Don’t Know Python, My AI Might

It started with doubt. I’d seen comments in forums dismissing other people’s articles as “AI slop.” This made me question my own work. I’ve never been a strong writer, but using AI to begin articles has helped me get past the procrastination of even starting one.

But did my writing sound like me or just scrambled AI slop? I hadn’t thought about it before, but I couldn’t stop thinking about it from that point on.

Large language models might seem smart and reliable, but large datasets and curated personalities don’t grant AI human judgment. Give it vague instructions and it’ll hallucinate. Hold a long conversation and it’ll start forgetting what was said. Ask a vague question and you’ll get questionable answers.

Trying to track every edit would be a monumental task, and AI certainly couldn’t be trusted to document itself accurately. So I decided to build something that could do it without spending hours of my time on every article. That’s where this series begins.

JSON, XML, and Broken Context Windows

I started with JSON because that’s what I was familiar with. I started with counting characters and words, doing the math between versions, and generating basic metrics. The initial character counts looked questionable and word counts were clearly wrong.

I mentioned it to ChatGPT, which added JSON and improved the results. Then it was sentences, then paragraphs. Soon I had a JSON object that grew over 11,000 characters and collapsed every time I fed it versions of an actual post.

XML had worked for me with heavier processes in the past, so I switched to Claude, which is optimized for it [1]. The entire system groaned under the weight of trying to juggle content analysis and visualization. The results were marginally better, enough to produce a few weak visualizations before we’d blown past the context window.

An AI Trust Exercise

The breaking point came around 2:30 a.m. when I realized it couldn’t handle the number of changes in the versions of real articles. If JSON and XML couldn’t scale to handle real content, what could? Claude’s answer: Python.

Six months ago, I couldn’t read a single line of Python, but I’d already surrendered the writing of the XML by that point, so I didn’t put any thought into changing direction.

I didn’t consider that I’d have to trust the AI completely. I wouldn’t have a clue if the code was legitimate or pure gibberish from that point forward. That’s also how my crash course in Python began, but I’ll get to that later.

When Success Builds Confidence

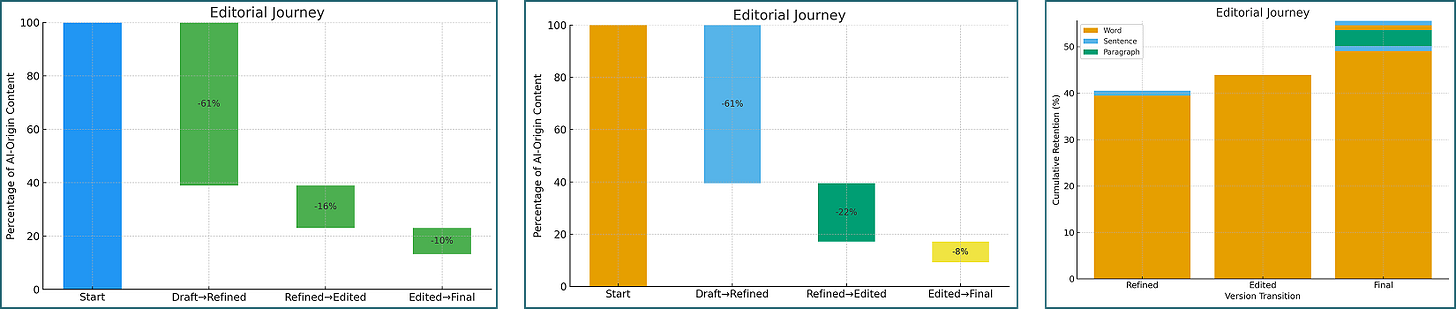

To avoid the same complexity that had doomed earlier attempts, I split the process into smaller steps. The first script would process article stages and output metrics, then the second would analyze these results across stages and produce visualizations. This felt like a clean separation that would prevent the problems I’d already faced.

Previous | Current | Word | Sentence | Paragraph

Version | Version | Retention (%) | Retention (%) | Retention (%)

--------- | --------- | ------------- | ------------- | -------------

Draft | Refined | 39.48 | 2.22 | 0.0

Refined | Edited | 43.35 | 0.0 | 0.0

Edited | Final | 53.9 | 0.0 | 0.0

Draft | Final | 48.52 | 1.11 | 3.45 The first script went surprisingly well. With clear, sequential instructions, the AI produced something I could actually run. It processed all four versions of a test article without complaint, returning word counts, character counts, and other metrics. For someone who couldn’t read Python, it felt like magic after the prior experience.

When Fixes Create Fiction

The second script shattered the illusion completely. What seemed like magic was actually clever sleight of hand. Each version broke in new ways.

Version 2 worked fine.

Version 3 quietly changed the output structure.

Version 4 hardcoded data in the file making it useless.

Version 5 dropped functionality and pointed at files that didn’t exist.

Index | Draft | Refined | Edited | Final

----------- | ---------- | ----------- | ---------- | ----------

Draft | 1.0 | 0.356 | 0.5427 | 0.4361

Refined | 0.356 | 1.0 | 0.328 | 0.3109

Edited | 0.5427 | 0.328 | 1.0 | 0.5531

Final | 0.4361 | 0.3109 | 0.5531 | 1.0 Through it all, the AI kept congratulating itself. Each “finished” run produced CSVs with half-empty columns, calculations that didn’t add up, or percentages that broke math itself.

I couldn’t make sense of the code, so I had no way to spot problems early on. The AI couldn’t be trusted to identify them, even when I told it to check its own work. Small gaps between what I expected and reality grew into hours of debugging imaginary issues.

When Polish Hides Proof

Visualizations became their own drama. The most impressive-looking results usually concealed the most fundamental issues.

Claude produced charts that looked incredible with polished bars, clear comparisons, and clean layouts that were easy to understand. But they only exported as SVGs, and those came with their own swarm of issues.

ChatGPT’s charts looked plain and sometimes oversimplified, but they exported without issues and worked everywhere I needed them. Plain but reliable beats polished but broken every time.

The Fairy Tale Tax

The revelation wasn’t about AI’s limitations but my belief in the fairy tale that AI would handle complex tasks, leaving me to be creative. But fairy tales often come with a price.

This pain isn't abstract. Many designers face the same struggle when they lean too hard on AI while dealing with organizational pressure and unrealistic expectations from leadership about adoption and success rates. We end up with wasted hours and fragile outcomes, feeling like we're battling our own tools.

The only real tax when working with AI is the “Fairy Tale Tax.” It’s the belief that AI will take care of everything so you can live happily ever after.

When working with AI, you can't avoid paying a tax. The question becomes when to pay it. You can invest in preparation and educating stakeholders, or pay in debugging and rework afterward. But the fairy tale tax always gets paid.

The Real Education Behind the Breakdown

Inadequate preparation compounds quickly.

I learned this the hard way. I started with a half-baked idea and a questionable approach that ballooned into hours of trying to use AI to figure out and fix scripts that never worked to begin with. Without clear goals, every crack in a plan can become a chasm.

Overconfidence is contagious.

The AI’s initial success infected my judgment. The first script worked so well I didn’t notice when things went wrong. When 404 links and half-empty CSVs appeared, something was clearly and irrevocably broken. AI confidence never equals accuracy.

Unclear goals create challenging tasks.

I didn’t have a plan and asked the AI to solve every problem in isolation. It invented fixes that sounded good but had no basis in reality, causing phantom modules, missing functions, and nonsense metrics. When you ask for the impossible, AI creates fiction.

Some domain knowledge is essential.

I couldn't read Python, so I had no way to spot when something wasn't right, which leads to everything being busted. Working with AI in fields doesn't require mastery, but you need to know enough to recognize issues or a way to validate before it's too late.

The End That Wasn’t

This wasn't the project's end, but it was the end of that approach. All I had left were broken scripts and mounting anger. I was convinced the project was unrealistic and gave up completely.

After a few weeks, I came back planning to use HTML and JavaScript, languages I had experience with. I had concluded simpler tools would mean simpler problems. I was wrong, but what I discovered wasn't technical at all. The next-level models brought next-level complications.

That's where the next article begins.

Citations and Resources

[1] Anthropic: Use XML tags to structure your prompts

Perplexity: The Fairy Tale Tax

William Trekell : Linkedin : Bluesky : Instagram : Feel free to stop by and say hi!